Provenance

Private collection, France

Exhibitions

Probably at the Exposition des Artistes Indépendants, Paris, 1934, either no. 2662 or 2663.

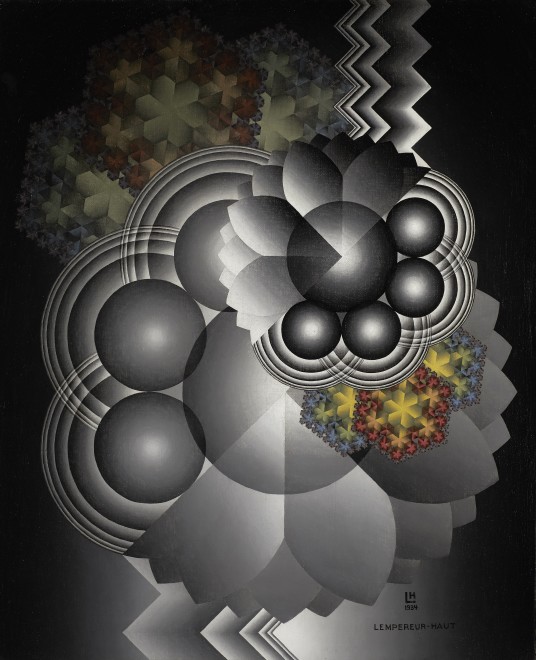

Lempereur-Haut (fig. 1) first took drawing lessons in his hometown of Liège at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and then took courses at l’École Industrielle concentrating on mathematics and geometry. He then worked as an industrial designer. Just before the start of the First World War, he received a grant from the city of Liège to spend two weeks in London. After he returned home, the city was occupied for four years isolating him from the outside world. He independently produced his first geometric painting in 1917, but it was only after the War ended in 1918 that he was able to see in reproduction abstract works by Kandinsky and others and further develop his own interest in abstract compositions. His artistic career commenced as an illustrator and print maker, and then in 1920 he and some other artists founded a futurist review called Anthologie. Here he published his first text on what he called “Art plastique,” writing what would remain his life-long approach: “For art one must synthesize. Be open; analyze the object to be represented; deconstruct it to the essence of form and color, the simplest elements. For the form, we have the cube and the sphere. For color, the primary ones – yellow, blue, and red.”

In 1923 he was married and for his wife’s political career, they moved to the Northern French city of Lille, where he remained until 1945. There he soon became part of a group of artists and writers called Vouloir who “sought to engage with the dynamism of modern life.” They had a group exhibition in 1925 to which the influential and innovative Czech painter František Kupka was invited to participate. Lempereur-Haut was still producing representative works, including even portraits, and in this exhibition he showed works of “stylized forms,” but Kupka exhibited works which were “resolutely abstract.” Meeting Kupka upon this occasion, Lempereur-Haut was persuaded by him to abandon figurative art and dare to produce only abstracts. Beginning in the same year the painter had his works included in the distinguished annual Parisian Exposition des Indépendants. Then in 1932 he was invited to join the group of artists led by Henry Vierny known as the Musicalists, who attempted to capture in paint the effects of music. Lempereur-Haut was pleased to exhibit with them in Paris and elsewhere, but maintained that he did not agree with their theories. When his wife became a delegate to the National Assembly in 1945, Lempereur-Haut and his family moved to Paris. There in 1946 he became an early member of yet another group of abstract artists known as The Association de Réalitiés Nouvelles. With them and independently at various Parisian galleries, Lempereur-Haut continued to exhibit his ever more complex works until he returned to Lille in 1959. Despite vision problems late in his life, he remained productive and engaged, happily able to participate in a major retrospective of his work in Lille in 1985, shortly before his death. Lempereur-Haut is regarded as one of the leading representatives of the abstract movement in Belgium and Northern France, and, as the Bénézit dictionary of artists nicely summed up his career: “He remained loyal to a radical abstraction of complex geometry with a precise technique and refined sense of color which gave expression to a cosmic poetry like shards of gems.”

Abstraction in Europe in the first part of the 20thcentury took many forms from Cubism to Vorticism, to Divisionism, Orphism, and Futurism. There were a number of remarkable individual artists who perfected personal abstract styles such as Hilma af Klint, Kandinsky, Klee, Malevitch, Delaunay, Mondrian, Gabo, and Kupka. The last of these, Kupka (1871-1957), who first went to Paris in 1899 was not a Cubist but rather inspired by Seurat’s theories of color contrast began experimenting with prismatic colors in disc form. About 1913 he produced what Alfred Barr described as “probably the first geometrical curvilinear and the first rectilinear pure-abstraction in modern art." He then became concerned with a theory of cosmic rhythm that he believed regulated both the stars and the sea, and this resulted in flowing but balanced abstract forms, such as in his Bleus mouvants(fig. 2a). In 1931 Kupka was a founding member of the group Abstraction-Créationdedicated to the recognition and dissemination of abstract art in counterbalance to Surrealism. And in the 1930s he developed a version of abstraction employing the world of machines as the basis for his more geometric forms. In his paintings of this period, he distilled the contrast of circular and rectilinear elements into pure abstract compositions of great power (figs. 2b-d).

Lempereur-Haut could not help but be impressed by such forceful works by his “friend,” but his was a more refined, lyrical style based on nature, and it also owed as much to one of the least well known abstract art movements, “Musicalism,” developed by the French painter Henry Valensi (1883-1960) in the late 1920s. This was codified by Valensi and several other artists into a movement in 1932 when they created the Association of Musical Artists, began a series of Musicalist Salons, and published a Manifesto. According to this artistic doctrine, these artists sought to synchronize color and form on their canvases in the way a musician arranges sonic matter in direct relation with the emotions they wish to express. While the theory may have been a bit abstruse, Valensi’s musically inspired works (Symphonies and Fugues) have a brilliant, prismatic, stained glass effect and are notable for often integrating natural forms, especially flowers, plants, and sometimes stars (figs. 3a- e).

As mentioned previously, Lempereur-Haut claimed not to agree with the theories of these progressive artists and sought to develop his own particular vocabulary of abstract forms based on an individual mathematical system that he devised. These forms, although sometimes devoted to musical themes similar to those of the Musicalists (figs. 4a-b), often, as in the present case, evoke the pattern of snowflakes and combine geometric and natural shapes in a kind of kaleidoscopic vision rendered in very subtle colors. Lempereur –Haut explained his singular process of creation:

I play with geometric figures and they become what they wish. When I begin a painting, I do not know what it will become. I make many sketches and calculations. If it resembles something, I give it a title when it is finished.

He painstakingly prepared preliminary drawings in colored pencil and with collage before actually painting his canvases, describing his approach as follows:

To make a painting, I proceed in a manner that is not typical of painters. I work like an industrial designer on white paper with my T-square, my compass, and my ruler. When I begin a painting, I do not know where it will go; there is no inspiration. But when I begin, it is already finished.

Here, carefully constructed in dynamic, overlapping shapes, which, as the title, Flowers, suggests, the forms do create the image of abstracted blossoms. This motif occurs in other of the artist’s works of the 1930s (figs. 4c-d), but he also played with curlicues, hearts, stars, and colorful squiggles (figs. 4e-h). Gradually he abandoned such specific subjects for more generalized ones identified simply as Compositions(figs. 4i-l). Always he incorporated his LHmonogram prominently on the ground of these compositions.

This painting is dated 1934, and an inscription on the back indicates that it was shown in an exhibition of La Socièté des Artistes Indépendants in Paris. In fact Lempereur-Haut did exhibit two works at that Salon, both titled Fleurs, and he did so again in 1936. It is impossible to say which works were shown on these occasions, but it seems safe to assume that this major painting was one of them.