Provenance

Private Collection, Basel, Switzerland, by 1940

Exhibitions

Niklaus Stoecklin, Kunsthalle Basel, 1940, no. 144.

Literature

Hans Birkhäuser, Niklaus Stoecklin: Neundvierzig Wiedergaben von Gemälden und Zeichnungen, Basel, 1943, p. 11 and ill. 27.

Niklaus Stoecklin (figs. 1a-b), whose father was a businessman, was born into a family of artists, including his sister and uncle, in Basel, Switzerland and became one of that country’s outstanding twentieth-century painters and designers. From his grandfather, an entomologist and scientific illustrator, he derived a passion for close observation and analytical drawing of natural elements. To further his training he went to art school in Munich in 1914, but the outbreak of the First World War curtailed his studies there, and he returned to Basel. He served in the Swiss army stationed in the Ticino, near the Italian border. He then attended the Academy of Fine Arts, but also studied with his uncle, the painter Heinrich “Haiggi” Müller (1885-1960). His first exhibition of paintings and graphic arts was held in 1915, and his first success was in 1917 with the painting The Red House (fig. 2). Between 1917 and 1919 Stoecklin immersed himself in studying late Gothic Swiss masters, such as Konrad Witz, and also at the same time worked with the founders of the Swiss Expressionist movement. He was involved with the Basel group of artists known as Das Neuen Leben (The New Life) who were intrigued by Cubism, Futurism, and Orphism. On a more practical level Stoecklin began to earn a living by designing posters, and he turned out to have a brilliant, bold graphic sensibility that led to a long career, producing poster designs for all kinds of products and institutions including his hometown (figs. 3a-d).

From about 1917 Stoecklin traveled widely, visiting Italy, Tunisia, Egypt, Greece, and England, and he painted many scenes set in these foreign locations (figs. 4a-d). During the 1920s the artist began painting unsettling figurative subjects and moody still lives (figs. 5a -h), which were quite close to the German art movement dubbed Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) to identify it as a post-expressionist approach, presenting an unsentimental realism addressing contemporary culture. It consisted of a diverse group of artists. While it’s most famous representatives - Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and George Grosz - focused on social and political subjects, and others like Christian Schad, Georg Scholz, and Herbert Ploberger were known as portraitists, still others concentrated on still lives and to a degree embody the aspect of Neue Sachlickeit often identified as “Magic Realism” that presented ordinary elements or everyday objects in a manner that was tinged by the strange or fantastic. Among these German advocates of the New Objectivity in still life painting were Josef Mangold, Georg Schrimpf, Anton Räderscheidt , Georg Scholz, and Franz Lenk (figs. 6a-f). Their choice of subject matter, including morbid flowers and exotic cacti, that also figure in Stoecklin’s work (figs. 7a-c), was undoubtedly part of a search for calmness, harmony, and timelessness in the midst of the turbulence of the Weimar Republic.

Although Stoecklin was to be the only non-German artist represented in the ground-breaking Neue Sachlichkeitexhibition held at Mannheim and Dresden in 1925, there were, in fact, a group of other Swiss artists who followed this route, and, like Stoecklin, created evocative still life compositions. These Swiss Neue Sachlichkeit artists included Eduard Gubler, Wilhelm Schmidt, Felix Paravicini, and Aimé Victor and François Barraud (figs. 8a-e ). But it was Stoecklin who emerged as the leading Swiss painter of his generation. Already in the late 1920s Swiss museums presented exhibitions of his work, and he was also commissioned to paint murals. Between 1927 and 1930, Stoecklin often visited Paris, and some elaborate scenes set there would appear in his paintings (fig. 9). In 1933 Stoecklin was the subject of a monograph in French by the distinguished, Polish-born art critic Waldemar George (1893-1970), who noted the painter’s “melodic quality” and his “mixing of reality and unreality,” deriving from “a poetic approach in which the arbitrary power of the imagination reigns as the absolute master,” in what the writer described as Stoecklin’s “tableau-microcosme.”

Stoecklin continued to produce still life compositions as well as figurative studies and landscapes for the remainder of his life (figs. 10a-i), even when in the 1940s and 50s, he worked almost exclusively on book illustrations and his advertising graphics. He also became a popular professor of the graphic arts at the Schule für Gestaltung in Basel. He died in 1982, but his fame has continued to grow, and exhibitions devoted to him have been held in 1997, 2013, and 2017.

As Hans Birkhäuser, who included our painting in his 1943 study of the artist, observed, Stoecklin’s “still lives account for his best works.” Perhaps inspired by examples produced by his uncle (figs. 11a-d), he gave considerable attention to this facet of his art where he could employ his meticulous technique and creative imagination to capture a whole range of varied surfaces and textures. The very first article published in 1926 about Stoecklin had tellingly described him as “a new Old Master,” and it is evident in looking at some of his work (figs. 12a-b) that Stoecklin was inspired by the example of various Dutch seventeenth-century masters (figs. 13a-b), whose paintings he must have seen in the various museums he visited. In addition there was a Swiss realistic tradition of still life traceable back to the eighteenth-century artist Jean-Étienne Liotard and into the nineteenth century with Albert Anker (figs. 14a-b). Stoecklin’s exploration of still life themes found its fullest expression in his paintings of the late 1920s and into the 1930s in which diverse, even peculiar, groupings of mundane articles are invested with a haunting presence. He often chose to contrast humble objects of everyday use with flowers or unusual natural elements like sea creatures, insects or crystals and precious stones (figs. 15a-g).

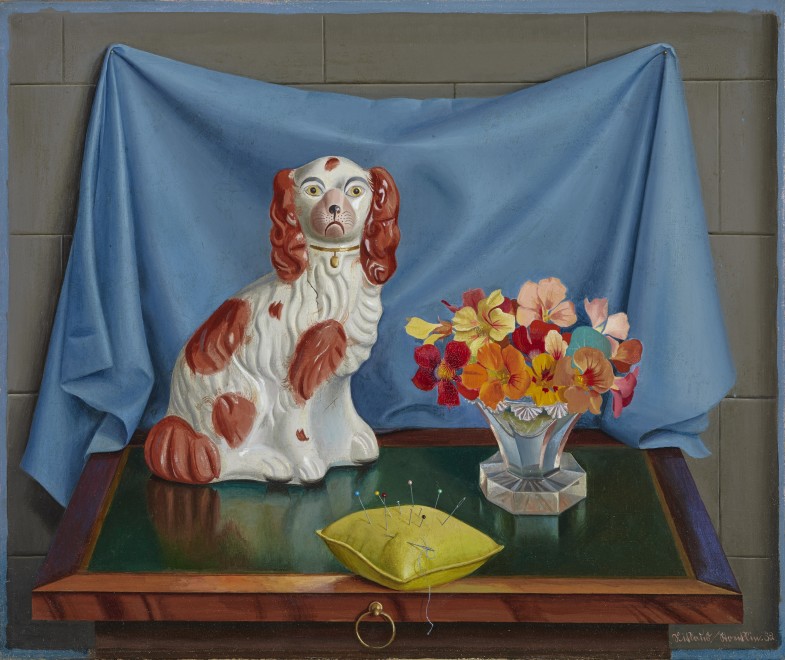

In the present painting the three disparate elements set on a desk top and arrayed before a blue cloth are a Staffordshire dog figurine, a small vase of flowers, and a pin cushion. The last two items would reappear in Stoecklin’s art (figs. 16a-b), but the nineteenth-century Staffordshire dog, which would have been one of a pair (figs. 17a-b), does not apparently appear ever again. Already in 1925, however, Stoecklin had made a large ceramic dog the centerpiece of another still life (fig. 18), and curiously his uncle included a porcelain dog in a much later still life (fig. 19). Stoecklin, by far the greater artist, was able when he chose to depict such popular items (figs. 15c- d, 18, and 20), to invest them, like he has with this Victorian collectable, with a disturbing presence. Its eyes wide open, it seems to stare out at the viewer, almost challenging us to appreciate its merit and acknowledge its presence. Likewise, the painter shows off his skill in the rendering of light reflected in the glass vase and the illusion of depth created by having the pin cushion just slightly protrude over the desktop. In an airless almost unreal space, the sharp pins inserted in the yellow cushion, the smooth glass surface of the vase, the brilliant flowers, and the polished finish of the ceramic dog all combine to create a strange, yet memorable, juxtaposition of objects which leaves us both perplexed and awed.