Provenance

Private collection, Germany

Until a recent retrospective exhibition in Germany, Richard Haberlandt was almost a forgotten artist. He was directly involved in the development of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) style which emerged in Weimar Germany in the 1920s as a challenge to Expressionism. As the name suggests, this artistic movement offered a return to unsentimental reality and a focus on the objective world, as opposed to the more abstract, romantic, or idealistic tendencies of Expressionism. This style is most often associated with portraiture, and naturalistic depiction reminiscent of the meticulous techniques of the earlier Old Masters.

Haberlandt first studied in Graz and then Berlin, but his professional plans were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. From 1915 to 1918 he was deployed both on the Eastern Front in Polan and the Western Front in France, and he participated in the battle of Verdun and suffered American air bombardment at Domary-Baroncourt. Haberlandt survived several gas attacks and was buried alive for three days. He returned from the War severely traumatized.

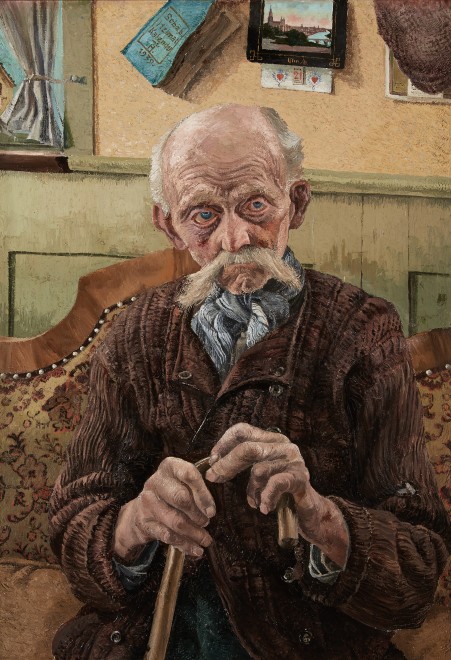

After the War, Haberlandt settled in the Thuringian city of Gera where he became close friends with the artist Kurt Günther. But owing to frequent hospitalizations due to depression and mental instability, Haberlandt moved to Bad Urach. Here, he continued to paint and occupied his time depicting the people around him, such as the old man portrayed here. Haberlandt was a master of traditional realist portraiture, but he moved away from the smooth tempera-like surfaces often associated with New Objectivity painters such as Otto Dix and Christian Schad. Always keen to experiment with color and thick paint application, his striking likenesses are unique and often express a dark melancholy, reflecting his own unstable emotional state.

The present work bears a striking similarity to another portrait painted by the artist one year earlier, and now hanging in the Stadtmuseum Klostermühle, Bad Urach. Both figures are elderly gentlemen seated in similar interiors. Each wears a sad, pensive expression – perhaps contemplating long lives nearing their end. Is it possible that these two men were residents in a sanitarium’s where Haberlandt once stayed?

Behind the sitter in this portrait, there is a clear reference to the passage of time and, perhaps faith: an image of the famous Ulm Cathedral is depicted on a hanging wall calendar. The 21st day of a month is clearly marked, but the specific month is illegible.